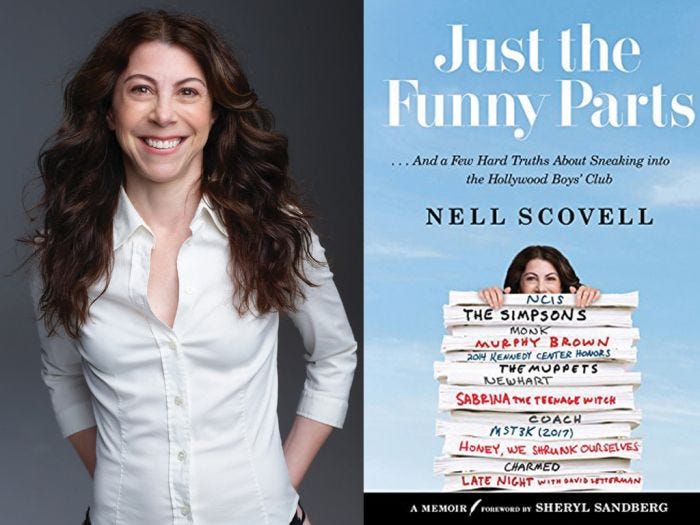

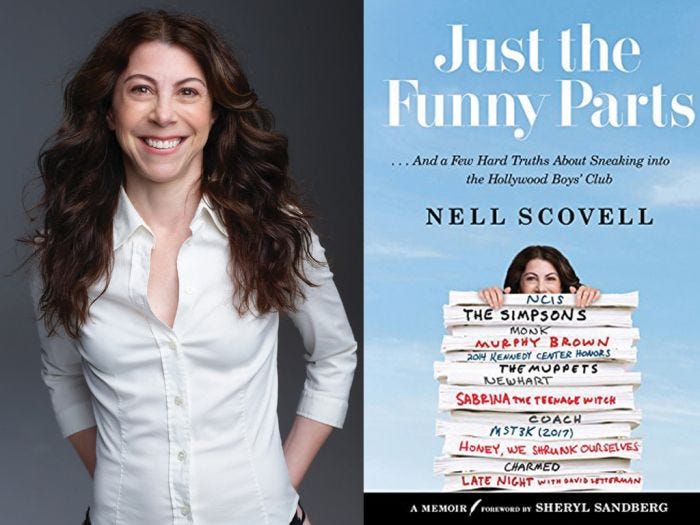

Image Credits: Robert Trachtenberg / Just the Funny Parts cover art, Harper Collins Publishers 2018

Over the holiday weekend, I finished Just the Funny Parts by Nell Scovell. The memoir was published back in March 2018 and branded as a scathing but funny insider look at “the hard truths about sneaking into the Hollywood boys’ club.”

Honestly, before reading it, I had no clue who Nell Scovell was. Just the Funny Parts had been a digital book sitting in my virtual to-read pile on my Kindle for the last 6-months. Something suggested to me, given my penchant for humor and feminism, and bought on a book-sale whim.

Once I got around to reading Just the Funny Parts, I was not disappointed. Well, I was. Not by the quality of the book but by the unfortunate experiences noted therein.

Unbeknownst to me, Scovell had some creative influence (as a writer, director, and producer) in many iconic television shows from my childhood and young adulthood: NCIS, The Simpsons, The Muppets, Charmed, Murphy Brown, Warehouse 13, etc. However, the work environments were often a challenge, especially since Scovell regularly found herself the only woman in the room, and rarely, if ever, were writers groups racially diverse or included anyone LGBTQ. Most writers' rooms were homogeneously made up of straight white males.

Per the book, the general belief is women, even those working in entertainment, are not funny. Because women are so often excluded, it is perceived as a favor when they’re allowed in. Women are expected to be grateful, no matter how dreadful or toxic the conditions are, and be willing to accept less pay or a lesser position without argument.

In this part memoir, part tell-all, Scovell chronicles— with delightful sprinkles of humor and biting wit— significant details about her personal life: how she first became interested in becoming a writer, the evolution of her career, and how she handled working in the highly-competitive, male-dominated entertainment field. Throughout this, Scovell was commonly identified as “a female writer” instead of just a writer; her gender was emphasized whenever it interfered with the boys club mentality the entertainment industry had long been operating under.

Some of the hurdles Scovell encountered were, at times, jaw-droppingly blatant examples of sexism, gaslighting, backstabbing, and double standards.

Emily Hampshire of Schitt's Creek (Instagram) reading reactions to Just the Funny Parts

I, too, keenly remember moments when I made many of the same faces seen here on Emily’s Instagram post, coupled with some audible, disgusted scoffs.

While settling into her office, Scovell’s first day on the job at Late-Night with David Letterman, one of her fellow writers stepped in to introduce himself. During this exchange, he made a stray comment.

“Before this is over, I will see a tampon fall out of your purse.”

Scovell posits this was him demonstrating what is called stereotype threat or making a pointedly embarrassing reference to reinforce her gender negatively. She was the only woman on the writing staff, after all. “Perhaps this explains why [he] went out of his way to remind me of my gender that first day,” in hopes of creating anxiety and inhibiting her ability to focus and perform well.

(e.g.) To throw her off her game.

In 2003, Scovell met with an agent to look over shows who were hiring. “As we went down a list, several times the agent noted, ‘They’ve already got two women on staff, so they won’t be looking to hire another.’ …this remark dismissed my skills and reduced me to my gender.”

In a meeting with 20th Century FOX, Scovell recalls an executive who said, “We’re big fans of yours. Are there any shows you’d like to work on?” Being a fan of 24, Scovell suggested the unthinkable. The executive's response, a matter-of-fact, “24 won’t hire a woman. They had one, and it didn’t work out.” One. Once. An officer of a publicly traded company flat-out told Scovell that because of her gender, she wouldn’t be considered for an interview. Once again, the remark dismissed her skillset based solely on her sex. This is illegal, but Scovell elected not to push the issue further, knowing what a Pyrrhic victory it would have been for her career.